mHealth & Future tech symposium

The future of mHealth

On the 22nd + 23rd of October Toni and Simon attended the mHealth symposium in Auckland, hosted by the University of Auckland.

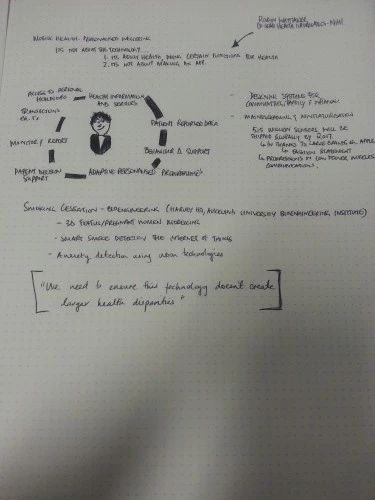

The way we access health-related services is changing throughout the world and New Zealand is no exception to this; we’re getting more and more access to medical technology for personal use, such as the Fitbit fitness tracker. The mHealth symposium brought together fifty academics from across the globe to present their various works in the areas of digital health interventions and education. The stage included NZ’s own Dr Terry Fleming, from Auckland University, and Dr Robyn Whittaker from the National Institute for Health Innovation (NIHI) whom presented their works on mHealth in both a national and global context. In particular, their projects focus on the evolving technology used within these products, becoming more integrated into our lives through fashion and accessible design.

We were lucky enough to attend the two-day event, held by the University of Auckland, hearing about the latest academic research and presentations in this space. Out of what we heard, here’s a summary of our highlights and the most contextually relevant content relevant to Lifehack’s work.

Dr Robyn Whittaker presented work on smart trackers that are becoming more about fashion rather than health, where the aesthetic value of the object is put before the functionality. However on the delivery side of tracking technology things are becoming more user-friendly and accessible in terms of cost: smart monitors in the form of a plaster that tracks heart rate and blood pressure.; this is likely to lead to new possibilities for data collection by and for health professionals and their clients as well as generally providing better access to wider markets.. Another example of innovation in delivery is the temporary tattoo temperature monitor which can measure temperature down to the level of changes within our cognitive exertion, tiny changes in temperature when our mental load fluctuates. This means we are now able to measure the tiniest changes of temperature in our bodies, enabling more accurate research into physical changes occurring during certain situations.

What’s required to help products like those become more established advances in batteries and power across all of these products. They require new properties such as being stretchable and moveable, making wearables much easier to mould to different forms, including our own anatomy.

Whilst a lot of this new technology is exciting and offers pathways forward, there are issues around passive data collection from a health perspective.How does this work with data retention laws?

Data collection is an inevitable part of the quantifiable-self movement. This particular conversation opens up discussions around the ownership of data, especially our own data — if you allow your health professional to monitor you, who owns the data that is collected? There appears to be a lack of consensus amongst health professionals, academics and patients alike as to who owns the data and how it can be used.

Dr Harvey Ho, Auckland University’s Engineering Department, along with students from Auckland University as well as three French universities have been using bioengineering technologies to create software and hardware solutions investigating the effects of smoking on foetal development. The team has managed to produce 3D models in high-fidelity (very detailed) representations of the foetus within the womb. This technology has the possibility of real-time use by midwives to show a more detailed representation the mother’s child, and the effects that smoking may have on the child.

The hardware component is made of open source and freely-available items (such as arduino, essentially a low-cost, tiny computer) that are assembled into environmental monitors — mainly focused on particle and smoke detection. The data collected by these small devices is wide enough to include very specific data points, as well as more general data to do with the foetus.

Future steps in this kind of technology will be to integrate with hardware that has an IoT (internet of things) component. Internet of Things is a new range of technology such as a fridge or washing machine that is connected to the internet. This will allow the healthcare provider to send data into the cloud, which in turn can be aggregated with other data to produce more contextually meaningful insights into mother and child health.

The project also investigated the different environmental factors in foetal growth, particularly looking at the different atmospheric conditions, such as gases present and air quality of the home. This is particularly relevant in New Zealand because 23.4% of the female population of New Zealand aged between 25-30 smokes, and the median age of mothers being 29.6.

On the second day of the symposium, various panel discussions provided us with new learnings and insights into the following topics

A panel of five were invited to answer questions from the audience.

How are we going to integrate emergent and new technology into the practices of clinicians and is this is a behavioural change on the service provider’s side? Co-designing with service providers can often alleviate the stresses caused when introducing new technologies, creating more of a partnership in care. Also co-design can be top-down from the organisational level, with implications around. A large piece of work seems to revolve around educating users. Acknowledging that there’s power in the informed user, allowing us to move around the barriers that our health services often impose (i.e. hacking glucose monitors).

Big Data, the concept of amassing sets of data which are many times larger than traditional datasets, has potentially huge public health benefits, but how are we going use it? When tobacco, alcohol, and advertising agencies are using this data to their advantage, it might pose threats for the general public . There’s opportunity for collaboration in this space, in particular between x and y. The health system needs to move out of 19th-century thinking and into an environment where we’re using this data on a daily basis to improve clients’ health. Currently researchers are using big data to tackle viral disease but it could be much more on day-to-day basis through the wider real-time collection of patient data.

Working with commercial products is challenging because it’s difficult to get access to the backend and raw data that these wearables provide. The main reason for this is the commercial nature of the products, and companies don’t want to allow complete and unsecured access to their platforms.

Can you get sued by companies for apps like Foodswitch?

Foodswitch is an app allowing you to scan the barcode of a product and then search for a healthier alternative. All of the data that is used in Foodswitch is public domain, and uses existing government standards to classify food items as either healthy or not. Food manufacturers are often getting in touch to update their products’ information, especially if they change any given formula. One of the most powerful elements of this is the end user and the food companies are updating the database constantly.

What’s next?

The symposium was a great introduction for the wider health research community for the different technologies that are either being worked on or already in the market. What the next steps are for this are not clear. Lifehack is interested in how these technologies can be integrated into the wellbeing of young people across New Zealand.

Do you have anything you’d like to say about this? We’d love to hear from you about mHealth in your area of the world – we’re excited to find out more about what kinds of programmes and pieces of technology are working for you and your communities.